by Connie Brenton & Sebastian Hartmann

It’s fairly plain to see that the nature of knowledge work at businesses across the globe is changing. The Fourth Industrial Revolution – the digital revolution characterized by a fusion of technologies blurring the lines between the physical, digital, and biological spheres – is heavily impacting practically everything businesses do:

- what they need to get done;

- how they are getting things done;

- who is doing them;

- where they are doing them;

- how things are prioritized, and

- how quickly all of this is evolving.

What’s not so obvious is the downstream impact on lawyers, management consultants, tax advisors, accountants, creative agencies and other professional service providers (“PSFs”). Established and new firms alike are leveraging a flood of new and often digital business models and are relying increasingly on data and AI-driven solutions, products, and services.

Despite immense pressure to transform professional services (as reflected by the growing number of news headlines, reports, discussions, and events on the topic), most PSFs fail to realize the full impact this paradigm shift will have on their business models, their organizational structures and processes and, of course, their financials. Instead of responding quickly and thoughtfully to these threats, most PSFs continue on their old and well-trodden paths.

One key reason for this failure to act:

The new forms of competition and the underlying shifts in client demands are “invisible” to traditional PSFs.

Why are they invisible? How can they be invisible? Conversations with typical clients for professional services (e.g. in-house counsel, top management, functional department leaders, and especially the procurement professionals) reveal a tectonic shift in the nature of client behavior into which PSFs have no visibility: Clients are shifting their spend – slowly and, in many cases, subtly. They are switching to new or different types of professional services providers and they are shifting spend into completely different procurement categories. Most importantly, the majority of these changes are taking place without PSFs having any visibility into the fact that the work exists at all or having any chance to bid on it. Here are some examples:

- Projects of all kinds are now often scoped and managed by in-house consulting groups.

- More (and more sophisticated) legal work is being done inhouse, is being automated, or is being eliminated by accepting more risk.

- Better market transparency (through marketplaces and social media) reduces demand for top established providers: the rising marketplaces provide plenty of options and transparency regarding quality and capacity, often even more accurately and faster than big firms can coordinate their own staff.

- Consequently, more and more freelancers (gig workers) are filling the needs for expertise and capacity.

- Legal spend is being shifted to alternative legal service providers or even consulting firms, especially when it comes to process optimization, digitization or automation within legal operations. The legal department of NetApp was recently recognized as an excellent example at the forefront of this evolution. One key takeaway: NetApp’s business issues are triaged in a way that fewer of them reach lawyers’ desks – both in-house and external.

- Data gathering, cleaning, enrichment, analytics, and visualization work of consulting firms is being replaced by technology/software providers – and thus even moves outside of its originating spend category. It is regarded as a “technology” problem – not consulting work. From a consulting firm’s point of view, the client’s “problem” actually disappears.

- “Implementation roadmaps” crafted by professionals across various fields often lead to actual implementation work. Even the big names in strategy consulting are said to make more than 70% of their revenue through implementation type projects. However, this important work (especially for outcome-focused clients) is gladly picked up by technology providers and their so-called “customer success” or “user adoption” teams these days. After all, it is their technology that is being deployed, so they are keen to enable consumption and thus revenue. Again, this spend leaves the professional services bucket and gets allocated in technology or even training or HR-related categories. Traditional consulting firms can be left empty-handed at the sidelines.

- Insights and benchmarks are available from “knowledge-as-a-service” providers. For example, the research and advisory firm Gartner has developed tools, knowledge bases and CIO collaboration forums that address the needs of CIOs in real-time or even before issues arise. Gartner can deliver insights and value ad hoc via flexible subscription models and platforms. And this makes Gartner or its peers the first (and sometimes the last) place a CIO goes for any question as soon as it arises: CIOs can get answers to their problems quickly, conveniently and long before the “trusted consulting partner” might ever get a call. Clients‘ spend for these types of services is often classified as an information service, a database or portal access – not advisory. But where does the line blur, right?

The list goes on.

What’s clear from these examples is that the shift in client demand and spend happens between players who don’t view each other as competitors. Many PSFs, bound by the inertia of not evolving their business model or service portfolio for decades – as well as clinging to decades-old management traditions – not only face shrinking pools of demand and decreasing margins, they may even face extinction in the long run.

It is a typical industry transformation pattern.

The market growth for many industries and firms since the Financial Crisis of 2008 has concealed a great deal of evolution: That façade of general growth provided a forgiving environment for many firms to succeed—and has tricked leaders into believing that they and their firms could succeed too without doing anything differently.

Unfortunately, most firms have failed to find new ways for monetizing their innovation, design and development efforts, their increasing use of technology and thus ultimately their IP. But this neglect of the potentially more scalable old, updated or new assets in combination with dramatically changing and technology-impacted core activities (all the way from sales, delivery into operations, support, etc.), may signal exactly what Anita M. McGahan has brilliantly described as “intermediating industry change” (in her article in Harvard Business Review):

“Executives tend to underestimate the threat to their core activities by assuming that longtime customers are still satisfied and that old supplier relationships are still relevant. In reality, these relationships have probably become fragile. The value of core assets often escalates, which compounds managers’ confusion… During periods of intermediating change, pressure in the industry tends to build until it hits a breaking point, and then relationships break down dramatically only to be temporarily reconstituted until the cycle is repeated.”

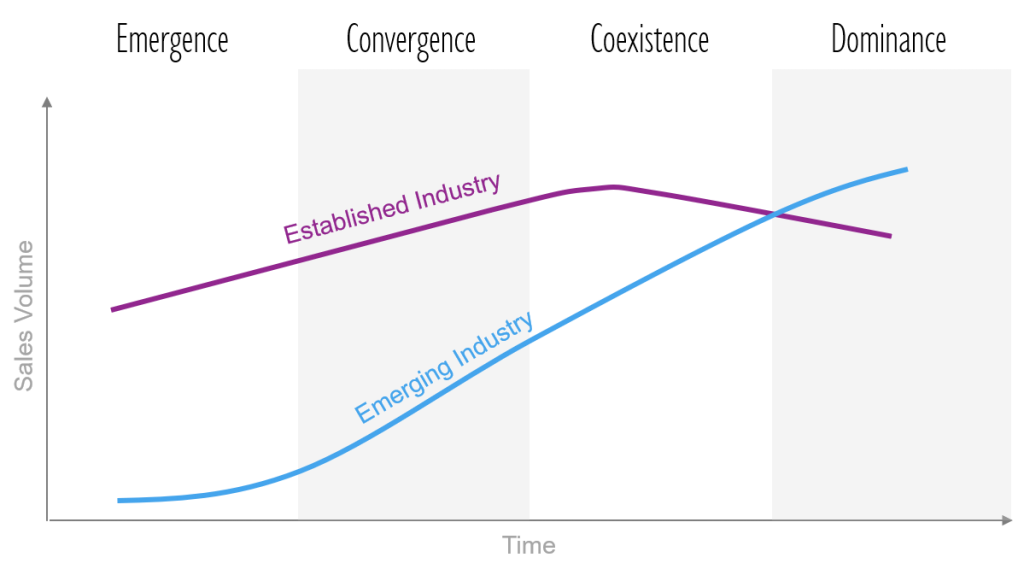

Figure 1: Visualization based on Anita M. McGahan “How Industries Change”, from the HBR October 2004 issue

McGahan’s alternative model incorporates the evolving behavior of buyers and suppliers. In the case of more traditional PSFs, it nicely visualizes their replacement by an emerging industry – the “next generation” of professional services, which operate across a much wider spectrum of strategic options and with a different self-perception.

To survive and thrive, professionals at PSFs need to re-think what their role is and how they interact with technology. This change may challenge the very core of many firms’ perceived identities and cultural histories. And this is exactly what their transformation eventually must be about: A new mindset reflecting a changing environment.

Acceleration in the COVID-19 aftermath

PSF leaders and managers need to recognize the depth of this paradigm shift – and adjust to an increasingly faster changing environment. At this very moment, in the face of the COVID-19 aftermath and a dawning global recession, most clients will become much more cost averse and price-sensitive – and open to solutions and providers capable of catering to these needs. This may turn out to be a clear advantage for more efficient and thus often more digital, alternative firms – even if they do not have the same reputation and brand value as established players. Furthermore, the whole world has moved to much more virtual collaboration models during the COVID crisis. To many firms’ surprise, this has worked out remarkably well – and was achievable faster for most businesses, functions, activities, and individuals than anticipated. Professional services firms and alternative providers, who have already invested in the required capabilities, technologies and ecosystems, may use this window of opportunity to outpace their more traditional competitors.

Jumpstarting the transformation journey

So, how should established law firms, consulting or accounting services providers evaluate this situation for themselves? Where should a traditional firm begin its transformation journey? The best place to start the search is probably a client conversation – but not just with the firm’s biggest and most profitable existing clients. These clients may have very little interest in finding alternative solutions – because they are quite satisfied with the way things are being done today. The right counterparts for this conversation should rather be outside your typical target group.

For example: A law firm should not just talk with the general counsel of an existing or target client – but rather the business leadership, the C-level suite, the legal operations managers or even Procurement. This search is not about the typical expertise, experience and credential show-off, it’s about defining the business of a professional service firm based on a clear understanding of current and emerging client business challenges and issues – and how they can be addressed, resolved or even dissolved. The resulting solution portfolio (both existing and potential) of a professional service firm then provides the starting point and canvas for defining its strategic path into the future. Traditional players may even have some advantage by leveraging their existing broad client network and relationships for these conversations – and relying on their reputation and brand for “getting things done,” even when providing new offerings or delivering solutions in novel ways.

This market lens should also be complemented by a critical assessment of the impact of technology on the different solutions, services, and products of the PSF. Across professional services, we can see the wildly expanding fields of technology applications and adoption – from anything as simple as basic collaboration tools to automatic workflows to advanced machine learning, or even artificial intelligence. The implications of these technologies range from changing client engagement models, creating new solutions (services, products) and evolving operating or even business models. PSFs must consciously build an ecosystem of technology partners who can help to see through the hype, and who have the necessary capabilities and strength of vision to make things real.

The biggest challenge, however, is probably going to be the true commitment to change within professional services firms themselves and their willingness to replace existing ways of doing business with new approaches.

A conscious, open and curious look outside the traditional competition may generate this necessary sense of urgency and belief in the new opportunities of a changing market. After all, the emerging competitive landscape opens up a lot more options for strategic positioning, which many firms can embrace as their chance to outpace and out-transform the traditional big names in their old market niche.